“Most of us, male or female, work at full-time jobs that seem organized around a presumption that some wifely person is at home picking up the slack— filling the gap between school and workday’s end, doing errands only possible during business hours, meeting the expectation that we are hungry when we get home— but in fact June Cleaver has left the premises. Her income was needed to cover the mortgage and health insurance….In fact that gal Friday is us, both moms and dads running on overdrive, smashing the caretaking duties into small spaces between job and carpool and bedtime.”

— Barbara Kingsolver Animal, Vegetable, Miracle

At our daughter’s parent-teacher conference this week, I described her behavior at home: whining, fighting, sticking out her tongue, nasty under-the-breath comments, arms crossed, brow furrowed. She’s angry about everything. My behavior at home has also been marked by anger, shouting, crying, and muttering under my breath — I hate my life! I don’t hate my life, but boy is my family having a rough time adjusting to “the daily grind.” It has us bickering at breakfast and dinner (which is all the time we spend with each other now), rushing through bedtime routines to get exhausted children to sleep so we won’t hate each other so much the next day.

It blows my mind that most people in this country participate in the daily grind. No wonder we are an insane society! At the Bloomington Catholic Worker, we were busy but still we had more time with our children, more time for ourselves, and more time for serving others. I still struggled to parent my children well, but our daily lives generally felt more balanced. And I never ever uttered the words, “I hate my life.”

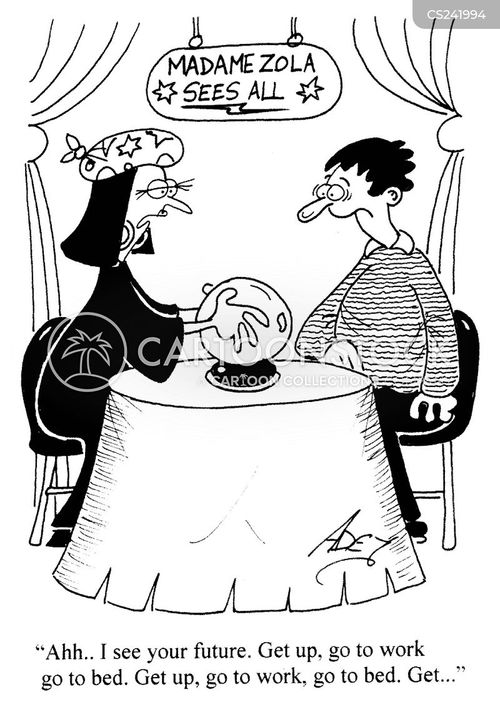

The question “Why?” comes to mind when I think about the daily grind. Why do we send our kids to school and rush off to work and then rejoin for dinner (often unpleasant), only to do it all again the next day? Yes, some people are pursuing fulfilling jobs and living out their passions. But even with the most fulfilling jobs, the daily grind asks so much of our lives. Never enough time with our families, never enough time for exercise or leisure or personal growth or other aspirations we’ve tucked away for retirement.

The answer is complex but largely wrapped up in security and stability. The daily grind, full-time work and full-time school, is how people afford housing and save for retirement and the kids’ college. It’s how we have to live to make ends meet. It’s very reasonable and responsible, but the outcome is so wretched. (Or maybe it’s just wretched for me and my family at this point in time….maybe it will get better?)

What does all this have to do with Common Home Farm? Part of our motivation for starting an intentional community farm is because we want a daily rhythm that is life-giving and balanced most of the time. We want to spend our days with our children (and with other people) engaged in meaningful, productive work. We are taking a risk in eschewing careers in favor of community. That risk is to let go of, or at least loosen our grip on the security of money.

This week I’ve been wondering if we are making the right choice. A friend of mine has community-minded parents who traveled the world seeking community instead of careers. Now they have no retirement funds and receive almost no social security payments. My friend and her husband work hard at full-time jobs to help support her parents. Her parents don’t have any other choice but to live with their children, which has been both a gift and a challenge. It makes me wonder if I should be less idealistic and more pragmatic. Should just stop my whining, find a career and start saving?

It seems to me that two truths are at play:

- We should work really hard now so that we can rest later.

- We should live out our values to the best of our ability each day.

I don’t think these should conflict with each other. I know we really want to do both: we want to work really hard to live out our values each day. I don’t know, however, that David and I will be able to rest when we are older. I don’t know that we will have any money in our bank account. I don’t know if we will be a burden on our children. I take some solace in thinking that we may have security on the land. That the place we hope to create – Common Home Farm – could be home to us and others for the rest of our lives. That the people who come to Common Home Farm, and the relationships we form, will be there to lift us up when we need help. We will have to work hard everyday to create this kind of security, but we believe it will offer us a daily rhythm instead of the daily grind.